(A Systematic Review of Anti-Tobacco Initiatives)

List of Abbreviations

- ACTT intervention programs denotes Acadian Coalition of Teens Against Tobacco

- ANOVA Analysis of Variance

- ASSIST means “A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial”

- CINAHL Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DARE Drug Abuse Resistance Education

- ERIC Education Resources Information Center

- ELISA Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- The HS Study intervention Hutchinson Study of High School Smoking

- HSPP Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project

- NHS National Health Service

- NICE means National Institute for Health and Clinical Guidance

- SCPPs Smoking cessation pilot projects

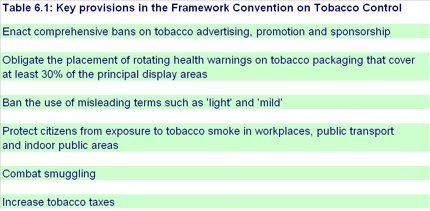

- List of Tables: Table: 1: Randomized Control Trials, Table: 2, Table: 3: % of children smoking by age England 2008, Table: 6.1: Key Provisions in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

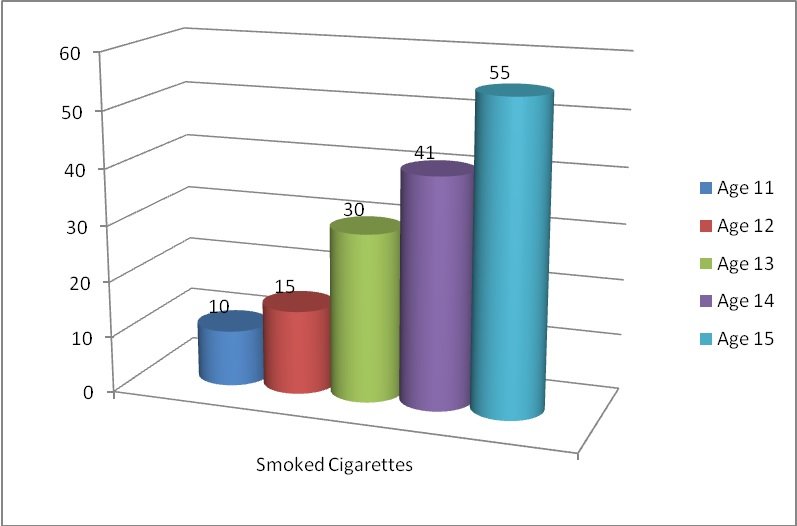

- Figure: Figure 2.1 Ever Smoked by Age (Adopted from NHS 2008 Survey)

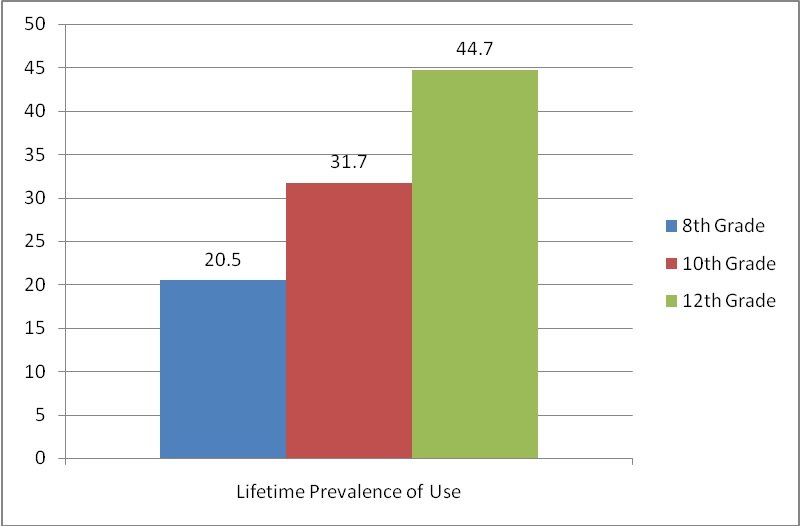

Figure 2.2 Lifetime Prevalence of Use for 8th, 10th, and 12th Graders (Observed percentage) – Adopted from the Monitoring of the Future Study, University of Michigan Research Institute

Figure 2.3 Trends in 30-Day Prevalence of Daily Use of Cigarette (Adopted from the Monitoring the Future Study, University of Michigan Research Institute)

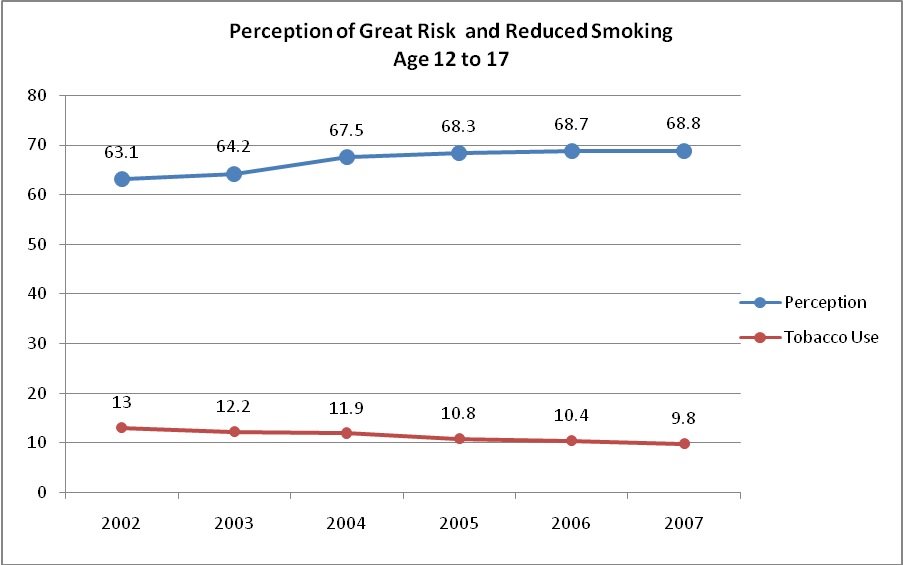

Figure 2.3.1 – The Relationship of Perception of Risk and Reduced Smoking Among Youth Age 12 to 17. (Data from Department of Health and Human Services 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Heath)

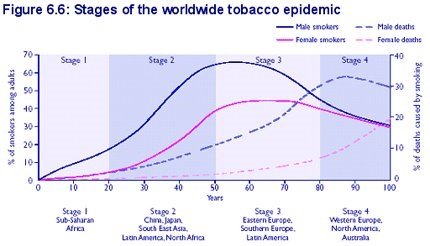

Figure 6.6 Stages of the Worldwide Tobacco Epidemic

Figure 6.7 Percentage of the Children Smoking Regularly by Age, England, 2008

- Abstract:

Background: Public health interventions is complex (Rothman et al. 2008, p.465) and may include programs to improve the health of special populations with a community, system-wide approaches that involve interactions between health care providers and representatives of community agencies, advocacy groups, and the media (Chalk & King 1998, p.207), and difficult theoretical issues influencing practice and evaluation of initiatives (Rothman 2008, p.77). The health effects of cigarette smoking have been the subject of intensive investigation since the 1950s (Elders 1994, p.15). Smoking kills more people than AIDS, diet and sedentary lifestyles, car accidents, alcohol, homicides, illegal drugs, suicides, and fires combined (Edlin & Golantry 2009, p.397; Boyle 2004, p.281). Today, research is largely directed at young people as the onset and development of cigarette use occur primarily during adolescent. The health consequences of smoking among young people are considered of great public health significance because results of investigations of the health effects in school-age youth revealed the adverse effects of smoking during childhood and adolescence.

Objective: The primary and sole objective of this systematic review is the review and redemption of useful information and data with the aim to attain complete success in smoking cessation and control interventions amongst young people.

Method and Data Sources: The secondary data for this particular study on public health intervention due to smoking amongst young people and its preventive measures is comprehensively collected from the following sources:

- the authorized and authenticated research bases, press releases, surveys and as well as many other syndicated data source

- the inexhaustible information, facts and figures provided at the hospital and medical centre’s website, resource centre and even declared data and internal survey results

- the government declarations and census data

- the infinite information bank through the internet

- the relevant medical books and journals available in plenty at important libraries and medical book and magazine stalls

Like any traditional reliable data sources, internet at the current scenario has invariably proven to be as the extensive, expansive, exhaustive and excellent resource of dynamic, authenticated, and qualified information bank, of course with its equal share of advantages and disadvantages.

Study Selection & Data Extraction: These readily accessible and timely updated secondary data resources are analyzed on the basis of systematic review in the following manner:

- Fundamental for identifying, describing, formulating and ascertaining the problem solutions, conjectures, speculations or any divergences

- Rationale for scrutinizing the true insight and philosophy

Data Synthesis: In the very short limited period of time, to delve deep into the mind of the matter and to equalize it to the reactions and responses addressing global clinical case environments in regards to prevention and cessation of smoking amongst young people, the unbiased data was collected and coordinated, planned and programmed as such to the best in line with its reliability and authenticity. To arrive at a universally accepted truth secondary data are chosen as such that equilibrium is maintained in terms of age, gender, marital status, education, economical and socio-cultural conditions. Due congruence is restrained in respect to the confidentiality and privacy rights of the secondary data resources without having the slightest chance to divulge in public the shared views which may pose a conflict of understanding otherwise.

Results: The media campaigns adopted by the Johnson et al. (2009) in their intervention program may have brought some positive results. However, exploiting informal channels and peer influence in addition to Social Cognitive Theory and Motivational Interviewing although helps the intervention reach more people with non-smoking messages; it is not clear if it has a direct effect on smoking behavior.

Conclusion: Although with limited participation caused by various limitations such as venue, availability, and budget, the use of media as the primary intervention tool helps the program work best and attain at least a realistic result. However systematic reviews pointed out that out of diversified results particularly cognitive-behavioural procedures and primary school level educational clinical environmental case practice and setup are comparatively effective and prospective towards attaining the target of smoking cessation interventions amongst the young budding generations. Furthermore cessation surveillance programmes should be systematically implemented and practiced to arrive at the target aim of complete abstinence from smoking amongst youth.

Keywords: public health, young people, tobacco use, prevention, cessation, smoking, intervention, smoking statistics, prevention, prevalence, better practice

Chapter: 1

Introduction

This chapter gives an outline of topics that are important to include when doing comprehensive analyses of public health initiatives. For various people, public health conjures up different ideas, and it can imply different things in different situations, but it is better described as an aim of enhanced health conditions and health status that can be accomplished by the efforts of all of us (Turnock 2004, p.27). In several cases, public policy seems to be unique, and public health programs have become significant contributors to health progress, with the potential to contribute much more in the future. Since most public health systems are defined by their inputs, actions, results, and effects (Novick et al. 2005, p.497), assessment is generally recognized as a conceptual approach to data management as part of the quality assurance method.

Evaluation is an essential component of public health practice (Stellman 1998, p.30) and evaluation of public health interventions is necessary as without sufficient evaluation, the effectiveness of public health interventions cannot be assessed and assured. In contrast, with sufficient evaluation, the design and deliver of future intervention can be modified in the light of the successes and failings of past efforts (Lin & Fawkes 2007, p.115). A process attempts to determine as systematically and objectively as possible the relevance, effectiveness, and impact of activities in light of their objectives (Stellman 1998, p.30). Public health initiatives or health promotion in general, employ a broad range or mixed methods to accumulate data thus a number of design strategies for evaluation have been developed (Rothman 2008, p.78). Evaluators adopt different approaches depending on the questions at hand. Some are concerned with the strategies and processes that are used to implement programs. Others are more interested in documenting the immediate effects of programs or examine the long-term effects and the extent to which program aims have been met (Lin & Fawkes 2007, p.116). In view of these complexities, evaluation of public health initiatives may require the use and expansion of existing guidelines (see Section 1.4 “the review question, scope and planning”) to produce a truly systematic review. In the literature review, all of the evaluations are systematically analyzed, assayed, and evaluated in order to arrive at the best available methodologies for smoking abstinence in young people by public approaches through a coordinated framework of systematic review. The aim of this chapter is to present crucial and relevant concerns surrounding public health programs that should be taken into consideration during the evaluation phase, a systematic review is required before any judgments are reached on whether programs can be extended, minimized, or sustained.

1.1 Background

People in Europe and America are concerned about the potentially harmful consequences of cigarette smoke, after the publication of several medical publications claiming that it can induce cancer of the lip, tongue, and lungs. Furthermore, a host of experimental studies have shown a number of health risks associated with cigarette smoking. It has been linked to the progression of coronary heart disease, bronchitis, emphysema, laryngeal cancer, oral cavity cancer, bladder and stomach cancer, duodenal ulcers, and allergies (Edlin & Golantry 2009, p.396). Acute effects of nicotine can cause heart attack, stroke, and number of poisoning and deaths from ingestion of nicotine were reported including acute intoxication in children after swallowing tobacco materials (Frances et al. 2005, p.112). Nicotine intoxication can cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and death due to paralysis of respiratory muscles (Frances et al. 2005, p.112).

“Tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States” (Marks et al. 2005, p.156) as it can cause diseases in nearly every organ of the body. In the United Kingdom, the Health Education Authority survey in 1996 found that 24 % of girls aged 15-16 smoked on a daily basis compared with 15% of boys (Coleman & Hendry 1999, p.123). Smoking contributes to 17 percent of all women’s deaths and significantly to at least one-third of all cancer deaths. The cumulative risk of death from lung cancer by age 75 in the UK in one large case-controlled study rose from 1% to 10% in female smokers from 1950 to 2000, as compared with a rise from 6 to 16% in male smokers. Smoking prevalence in the United Kingdom has been measured regularly since 1972 as part of the General Household Survey. These survey shows that the prevalence of cigarette smoking on adults fell substantially in the 1970s and early 1980s but in 1998, concerned with the rising prevalence on schoolchildren ages 11 to 15, the UK government set out a comprehensive strategy to tackle smoking in its White paper “Smoking Kills”. Smoking prevalence increases sharply with age and in 2001, about 1% of 11 year olds smoked regularly compared with 22% of 15 years olds (Boyle 2004, p.211).

1.2 Justification for the Review

As there are 1.1 billion people aged 15 and older who smoke globally, and 300 million of them live in developing countries, the issue of cigarette smoking and tobacco-related illness is not restricted to the United States or Europe. As a result, 4 million people suffer per year from tobacco-related diseases, about one every eight seconds. The key explanation given for the huge uptick in tobacco-related deaths is that the long-term impact of cigarette smoking on certain young people will only become apparent today (Boyle 2004, p.281). As a result, where a substantial amount of young adults smoke in one region, there would be a significant increase in tobacco-related deaths 50 years later. According to estimates, smoking would be responsible for 60 million premature deaths in developing countries during the second half of the century (Ammerman et al. 1999, p.94).

Smoking can cause significant damage to children, including eye and throat inflammation, elevated blood pressure, respiratory and immune defects, and pre-cancerous gene mutations. Furthermore, starting to smoke at a young age increases the likelihood of eventually consuming illicit substances (Elders 1994, p.15).

The systemic assessment of social services was first utilized in education and public health, and substantial attempts have been made to reduce death and morbidity from infectious diseases by public health interventions (Rossi et al. 2004, p.8). Smoking is still a public policy concern (Siegel & Biener 2000, p.115) and a major public health issue with a variety of reported negative health consequences (Haldeman 2004, p.193). As a result, a variety of public health professionals have continued to implement smoking cessation initiatives to combat the harmful effects of cigarette use in adults and youth. For example, in the United States, anti-tobacco media efforts, a prohibition on smoking in public spaces, and a major tax rise on tobacco goods (Atun & Sheridan 2007, p.51), and in the United Kingdom, the 1998 Department of Health initiative “Smoking Kills” that actually established tobacco as a severe health danger (Atun & Sheridan 2007, p.51) (Griffiths & Hunter 2007, p.134).

Since young people are more concerned about their appearance and social standing among their peers than their wellbeing in the long run, smoking among teenagers has become a public health issue and a frequent subject of systemic analysis (Schneider 2000, p.228). Despite the increased usage of anti-smoking advertising ads, nothing is learned regarding their efficacy and the findings are sometimes contradictory. For example, neighborhood and school-based approaches outlined in a mass media initiative in Vermont, New York, and Montana decreased smoking initiation rates among teens, but failed to affect smoking behaviour among youths in southern California (Siegel & Beiner 2000, p.116). According to Koop (2004, p.244), one of the challenges with evaluating the results of smoking interventions is that some of these trials are sometimes badly planned, with flawed methodologies and quality control. After reviewing and analyzing a variety of assessment cases involving smoking cessation treatments for young adults, the most promising and successful cessation program is chosen and suggested for implementation in order to plan and orchestrate the most efficient and convincing smoking cessation intervention process.

1.3 Aims and Objectives

The primary review objective is to gather evidence systematically from existing studies to determine why young people smoke and how effective tobacco use interventions in preventing this dangerous habit.

1.4 Review Planning, Scope, and Review Questions

Addressing the scope of the review and identifying important questions are necessary before any meaningful review can begin, as they can affect the key areas specified in the systematic review protocol. In addition, considerations must be given to a number of relevant and experienced groups such as practitioners and members of the community affected by the intervention, to ensure all questions developed are relevant and useful to decision-makers.

The CDC or the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention developed a framework for public health initiatives evaluation in 1999, which may offer some useful guidelines. These guidelines contain six important elements and four broad standards for program evaluation. These elements include identification of stakeholders, description of the program, clear statement of evaluation’s purpose, accumulation of credible and important sources of evidence, justified conclusions including analysis, and sufficient mechanisms for feedback. The four evaluation standards are specifically focus in the accuracy of evaluation design and ensuring that it is working to its full potential (Turnock 305). The CDC was responsible for the creation of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services in 1996 to address a broad range of interventions, targeting communities and health care systems. This task force also provides public health decisions makers with recommendations on population-based interventions to promote health and to prevent disease, injury, disability, and premature death at the state and local levels (Sheinfield & Arnold 2000, p.77).

Another method aimed to address limitations in conventional experimental designs and seeking to understand better the ways in which programs achieve their effects in a particular context is the “realist” approach (Tones & Tilford 2001, p.176). The rationale for this approach is to understand what may work for whom in specific circumstances by identifying the desired goals, context variables, and the mechanisms which may or may not operate within the contextual circumstances. This evaluation process has been used in a number of interventions such as the UK Health Action Zone developments and smoking cessation interventions (Tones & Tilford 2001, p.177).

A closely related model according to Tones & Tilford (2001, p. 177) is the Theories of Change approach where theories are expressed in the form of causal relationships. The Theories of Change advocates that social programs entail theories of change about how a program will work, whether these are made explicit or are implicit. This evaluation method combines both process and outcome elements that is designed to find the extent to which the theory holds up when a programmed is implemented. Similar to realistic evaluation, the use of data collection methods is diverse. This type of evaluation methods were used to evaluate health promotion program undertaken by the Health Education Board in Scotland (Tones & Tilford 2001, p.177).

Although decision makers may allow an evaluation of health program for a wide range of reasons, typically evaluations are done to answer to basic questions. “Did the program succeed in achieving its objectives? And why in this case?” (Grembowski 2001, p.19). However, in other programs, decision makers may want to know more about program implementations than its success in achieving objectives since they see it somewhat premature particularly in new programs (Grembowski 2001, p.19).

These fundamental questions can be narrowed down into several specific questions to ensure the production of information that decision makers specifically wants. These questions can be in the form of “Did the smoking prevention program reduce cigarette smoking behavior among adolescent between the ages of 13 and 15?” Grembowski (2001, p.19) or “Under what conditions does it work and how much does it cost?” (Smith & Taylor 2006, p.170). However, in this systematic review, the underlying principle of the intervention is considered the most appropriate source of questions. For instance, tobacco prevention campaign under the CDC follows certain principles based on the guidelines set by CDC on school-based intervention on tobacco use. According to these recommendations, a school initiative can first implement and adopt a tobacco usage strategy, offer awareness about the harmful physical and social effects of smoking, instruct children from kindergarten through 12th grade, offer specific teacher instruction, pursue parental or family involvement, promote abstinence, and evaluate the intervention on a regular basis. According to this information, aside from the basic question to determine why people smoke? or the reasons for smoking initiation, the most appropriate questions in evaluating the intervention can be as follows:

- Is tobacco use policy developed, implemented, and enforced?

- Did it provide the right information to the target population?

- Are the children from kindergarten through 12th grade receiving the education required?

- Are parents or families involved?

- Does the program support cessation

- Is the program assessing itself regularly?

The ultimate goal or objective of this research study is to systematically review the smoking cessation through realist evaluation cases and answer the two primary basic questions, namely, “In what exact procedures do the interventions operate?” and “To what extent to they serve the objectives of the systematic review?” The aims are:

- Systematic scrutiny of the intervention procedures

- Any alterations or modifications necessary to expedite and support the aim

- The realist responses noted from the target audience, i.e., the youth and their acceptability

- The measures taken to standardize and stabilize the matter

- To estimate the achievement of the short- and medium-term objectives and the feasibility study

1.5 Structure of the Report

This study is broken down into parts. The first chapter includes the review’s outline, history, reasoning, preparation, scope, and review concerns. The literature review in Chapter 2 examines the incidence of smoking in the United States and the United Kingdom. The explanations why people smoke, as well as an analysis in behavioral modification and intervention efficiency. The evaluation portion of Chapter 3 covers the quest approach, inclusion and exclusion requirements, results that were discussed, assessment methodology, and analysis limitations. Chapter 4 contains the study’s conclusions, while Chapter 5 contains the debate.

Chapter: 2

Literature Review

2. Prevalence of Smoking in the United Kingdom and the United States

In 2008, a poll of 7,798 students from 264 schools across England found that 32% of students attempted to cigarette at least once, and 6% of students smoke at least once a week. The percentage of students who smoke ranges depending on their gender and age. Girls are more likely than boys to smoke (33 percent vs. 31 percent). Smoking rates rise with age, with one in ten 11-year-olds (ten percent) having ever smoked, relative to more than half of 15-year-olds (55 percent) (NHS 2009, p.9).

Figure 2.1 Ever Smoked by Age (Adopted from NHS 2008 Survey)

In the United States, tobacco use is generally more widespread than use of any illicit drugs. In the 2008 survey conducted by the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, 45% of 12th graders tried cigarettes once or twice and 20% have been occasionally smoking at the time of the survey. Surprisingly, 21% students even in the 8th grade have also tried cigarettes and 7% of them have been occasionally smoking (p.85). Cigarette smoking initiation according to the data from the 2008 statistics for eighth graders tend to occur particularly early. The peak years for cigarette smoking start during the 6th and 7th grades at 10% between 11 and 13 years of age. However, there are indications that a small percentage of students initiated smoking much earlier as 7.8% of eighth grader admitted they had their first cigarette by 5th grade (p.271).

Figure 2.2 Lifetime Prevalence of Use for 8th, 10th, and 12th Graders (Observed percentage) – Adopted from the Monitoring of the Future Study, University of Michigan Research Institute

Figure 2.3 Trends in 30-Day Prevalence of Daily Use of Cigarette (Adopted from the Monitoring the Future Study, University of Michigan Research Institute)

2.2 Reasons for Smoking

2.2.1 Family Inspired Smoking

There is a wide range of factors that impinge on, or affect young people’s health and one them is the family (Coleman et al 2007, p.10). In the NHS 2008 survey of young people’s smoking, drinking, and drug use, one of the main reasons found why young people smoke was family influences. Among those surveyed, 59% lived in households where no one else smoked, 24% where one person smoke, 13% where two people smoked, and 4% where there or more people smoked. Those who lived in a household where someone else smoke seems more likely to smoke as the survey data shows an increase in the proportion of regular or occasional smokers according to the number of smokers they lived with. Regular smoking increase from 3% (living in households where nobody smoked) to 21% in households with three or more smokers lived (NHS 2009, Statistics).

Another influence is the perceived family attitude to young people’s smoking. Although majority of families including those with three or more smokers are taking a negative attitude towards smoking, it appears that they are more lenient with their approach to stop their children from smoking. The result of the survey shows that the amount or the quantity of cigarettes a smoker would depends on their perceptions of their families’ attitude toward smoking. This is because, opposed to 52 percent of casual smokers and 73 percent of non-smokers, 39 percent of daily smokers said their relatives might want to discourage them from smoking. Furthermore, relative to 2% of casual smokers and 1% of non-smokers, 14% of frequent smokers believe their relatives will do little to deter them from smoking.

2.2.2 Convenient Sources of Cigarettes

Young people get their cigarettes from various sources such as convenience stores, bars, eating establishments, friends, and relatives (Slovic 2003, p.44). Despite the legislation banning the selling of tobacco to minors, children under the age of 16 purchase cigarettes from shops (44%) and vending machines (10%), according to the findings of a 2008 NHS study. However, other individuals, such as acquaintances (58%), relatives (10%), and parents themselves (63%) are the most popular suppliers of cigarettes, according to the results (6 percent ).

The proportion of young people buying cigarettes from the shop in 2008 decreased by 23% compared to the 2006 figure of about 78%. Similarly, regular smokers purchasing from vending machines dropped by 12% compared with 17% in 2006. However, the number of regular smokes who are getting their cigarettes from other people increased to 52%, which is 12% more than the percentage points recorded in 2006. The decrease in young people’s buying cigarettes from shops is attributed from the difficulty to purchase. This is because among those students surveyed, 57% of those who attempted to purchase cigarettes from a shop were refused at least once. Similarly, those regular smokers who purchased their cigarettes from vending machine dropped from 37% to 12% due to strict monitoring being implemented by National Association of Cigarette Machine Operators (NHS 2009, p.27).

2.2.3 Level of Perception on the Danger of Smoking

The degree to which teens feel these drugs can affect them is one significant aspect that may determine whether or not they will consume tobacco or alcohol (Department of Health and Human Services 2008, p.59).

Measuring certain attitudes and beliefs about tobacco use can help explain and understand why young people smoke. For instance, in the 2008 survey of the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research (2008, p.338), 74% of 12th graders believed that smoking one or more packs of cigarettes per day could harm them while 39% think cigarette smoking is harmless. Students still do not believe that smoking a pack or more is risky despite the growing health consequences of cigarette smoking. From 1993 to 1995, perceived risk of smoking decreased at all grade levels and became fairly level between 2000 and 2003. However, it has increased again from 2004 to 2006 for 12th graders but it has declined with 3.3% point drop in 2008.

According to the findings of the 2007 study, rises in the perceived probability of consuming a drug are often correlated with declines in the rate of current usage of that substance (Department of Health and Human Services 2008, p.60).

Figure 2.3.1 – The Relationship of Perception of Risk and Reduced Smoking Among Youth Age 12 to 17. (Data from Department of Health and Human Services 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Heath)

[Directly extracted from Smoking Statistics available online at the URL:http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/lung/smoking/index.htm]

[Directly extracted from Smoking Statistics available online at the URL:http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/lung/smoking/index.htm]

TABLE: 3: % of children smoking by age England 2008

| % of children smoking by age England 2008 | |||

| Age | Boys | Girls | Children |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| 14 | 6 | 11 | 9 |

| 15 | 11 | 17 | 14 |

| 11–15 | 5 | 8 | 6 |

[Directly extracted from Smoking Statistics available online at the URL:http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/lung/smoking/index.htm]

[Directly extracted from Smoking Statistics available online at the URL:http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/lung/smoking/index.htm]

2.3 Understanding Behavioural Change

Complex interventions are often led by a hypothesis, which may be helpful in forecasting results and deficiencies. Other rationalities, such as coping or enjoyment, can direct human actions (Earle 2007, p.134). For certain individuals, the position of smoking in stress belief, for example, makes it seem reasonable to continue smoking despite the fact that it is considered to be unhealthy. The theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Actions would aid the researcher in comprehending behavioral adjustment at the person level, when people’s intent to behave in such ways is the determining factor in whether or not they do so (Earle 2007, p.134). Furthermore, a person’s behaviour is usually affected by the assumption that if a given behavior is followed, a certain outcome will arise, and that the consequence would be favorable to health (Earle 2007, p.134). For example, if people think they may die early in the immediate future, they are more inclined to give up smoking. They might also have a more optimistic outlook about leaving if they think it would make them smell better and appear better.

Another influential factor is the person’s belief about what others think they should do and to their motivation to comply with the wishes of others. For instance, if a person who uses tobacco feels that most people do not use it and most of those whom he values think it would be better for him to give up smoking, they he is more likely to develop a subjective norm that favor giving up.

Theories of planned behavior can be helpful in developing an intervention intended to meet an individual’s needs. The theory emphasizes that a person’s belief about an issue is essential since their decisions to improve their health or not entirely depends on how he or she perceived the issue. In the “Stages of Change” model, the five stages of change were developed to explain how people are motivated to adopt norms that would improve their health. At the ‘pre-contemplation’ stage, an individual is at the point where he or she actually intends not to change or adopt any positive change in their behavior. In the following stages, people are “contemplating” or already considering adopting a particular behavior and making progress or “preparing” to have serious commitment to change. In the fourth and last stages, they begin to take “action” or start making changes in their behavior and try to “maintain” them eventually. According to Earle (2007, p.135), although some people may not move quickly than others and not always intend to move forward through these stages, the change model is considering the reality that people are predictable and normally move through these stages.

The stages in the Change Model can help public health intervention particularly those that involve behavioral change, to plan their approach. For instance, if an intervention to prevent tobacco use would consider the first stage of the model, their initial action will be to raise awareness and provide information on the health risk of smoking. Similarly, they would also try to encourage people to think about the pros and cons of their existing behavior and consider the health benefits of change. The public health intervention may consider the two last stages and support those who decided to quit and help them maintain it through constant follow-up.

2.4 Addressing the Quality of Intervention Delivery

Public health interventions are traditionally characterized in terms of levels of prevention. Primary prevention is an approach that is focus to ‘prevent’ the occurrence of a public health concern. Secondary prevention on the other hand is more focus on immediate responses such as emergency services, treatment, etc. The third level of intervention is an approach that promotes long-term care such as rehabilitation and reintegration (Krug 2002, p.15).

To determine if the intervention is delivered correctly as planned, knowledge of the campaign’s underlying principle is necessary since these would disclose how the program would plan and pursue its objectives. The ACTT Campaign was planned based on the results of a Health Habits Survey completed prior to launch, but the report acknowledged that it did not take into account the CDC or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance when designing target criteria for school-based smoking prevention initiatives. According to the CDC’s recommendations for school-based health services on cigarette use and abuse, school-based health initiatives may be able to inspire children and youth who have never attempted smoking to stay away from it. For those who have already tried, the programs should be able to encourage them to stop and refrain from further use. Additional assistance should be given to those who are unable to stop or quit tobacco use (MRWR 1994, p.9). Fundamentally, school-based programs according to CDC guidelines should succeed in attaining the following objectives:

- Reduce the rate of tobacco smoking to at least 15%.

- Reduce the number of adolescents and teenagers who start smoking cigarettes to at least 15%.

- Establish tobacco-free neighborhoods and incorporate tobacco-use education into both primary, high, and high school curricula.

The CDC thus recommends the following strategies for school-based programs:

- Establish and implement a tobacco-free school curriculum.

- Teach about tobacco’s short and long-term harmful physiologic and social effects, social impacts on tobacco usage, societal expectations on tobacco use, and refusal abilities.

- Have kindergarten to 12th grade instruction.

- Provide teachers with program-specific instruction.

- Seek parental or family involvement and assistance.

- Encourage school employees and students who use cigarettes to quit.

- Evaluate the tobacco-use avoidance initiative on a regular basis.

The tactics mentioned above are examples of the campaign’s strategy that must be implemented in order for it to be effective. The campaign must, in particular, adopt and implement a school curriculum that is compliant with state and local laws. Help students consider how cigarette usage leads to decreased endurance, stained teeth, poor breath, and social isolation, as well as the anti-tobacco standards. Let the youth feel that there are other ways for them to appear mature and welcomed by their peers besides smoking. Assist students in developing the knowledge and confidence to counter tobacco-promotional advertisements from the public, their peers, and their families. Teachers should be educated about the program’s basic ideas and reasoning, and parents or relatives should be involved in program preparation and reinforcement of instructional messaging at home. To assist those who need to stop smoking, have emotional reinforcement, anger control, and rejection skills. Finally, to evaluate the tobacco-use reduction initiative on a daily basis while keeping the above key questions in mind.

- Is the tobacco usage program being applied and executed according to plan?

- Does it promote the necessary awareness, attitudes, and skills to help people quit smoking?

- Is compulsory schooling given from kindergarten through the 12th grade?

- Do parents or families participate in the creation, execution, and evaluation of programs and policies?

- Does the service promote and help people who are trying to stop smoking?

These questions can be use to determine if the ACCT intervention was delivered as planned.

Chapter: 3

3.1 Methodology

Systematic Review is the organized methodology of systematically scrutinizing and speculating the varied different intervention evaluations – which in these regards are done here following the Cochrane Collaboration format by formulating in the form of:

- Systematizing a clinical issue

- Identifying and isolating selective studies

- Critical analysis and assessment of studies

- Congregating valuable information and databanks

- Assaying, analyzing and apprising the outcome

- Elaborating and elucidating the results

- Developing improved reviews

3.1 Selection Criteria

3.1.1 Inclusion Criteria

Credible studies published in English particularly those sponsored and funded by government health organizations. These include results of nationwide surveys on young people’s tobacco use and secondary research appearing in the published literature.

The study’s primary interest is on combustible tobacco products that are being marketed to young people through aggressive advertising on television, posters, billboards, and the Internet. It is beyond the scope of this review to investigate the ill effects of tobacco use on health, as it is more interested in factors that influence young people to smoke and the quality of intervention applied to stop it.

This systematic review is after the young members of the community or those who are still in school because they are the common objective of numerous school-based interventions aiming to prevent the use of tobacco among children and young people. For instance, the NICE or National Institute for Health and Clinical Guidance for public health interventions in the United Kingdom was created to prevent smoking on young people and supports a number of related government policies for children’s welfare such as the Children Act 2004 and the National Service Framework’s preventive efforts for children. In addition, it also supports school-based interventions such as “Smoking Kills” and the latest Department of Health national strategy for tobacco control. Similarly, school-based preventions were also launched in the United States based on the idea that schools have a role to play in reducing serious problem of smoking and tobacco use by young people.

The common initiatives of both countries were encouraged by the result of various studies from government agencies and non-governmental organizations, which suggest that more than 1,000 kids in the United States today are becoming regular smokers under the age of 18. The studies also suggest that the addiction rate for tobacco smoking is much higher than the addiction rates of alcohol and illegal drugs such as marijuana and cocaine. Moreover, 90% of all adult smokers started at a very early stage in their life and 20.4% of students studying in high school are current smokers when they finish high school.

Since public health interventions are complex and typically involves numerous components, this systematic review will only include interventions based on a single theoretical underpinning following the CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Even randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which are critically scrutinized in the process of this systematic review are studied to evaluate the effectuality of smoking cessation interventions amongst the youth. All RCTs are conducted with youth aged equal to or lesser than twenty years and extracted from journal studies between 2002 and 2006 and also inclusive of research in PubMed and PsycINFO from 2001 to November 2006.

3.1.2 Exclusion Criteria

This study excluded sources that were not published in the English language, narrative reviews, too few samples used to represent the majority, newspaper and magazine reports, factsheets, and conference proceedings.

3.2 Search Strategy

This study was prepared using a structured method of literature scanning and compilation. Language and publishing date were used to narrow down the results.

3.2.1 Principal Sources of Information

The following websites and other sources were search using the restrictions mentioned above and search terms specified in the following section.

- Drogues, sante et societe, Vol. 6 no 1, juin 2007 Supplement II

- PubMed Central

- PsycINFO

- Jϋni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic Reviews In Health Care: Assessing The Quality Of Controlled Clinical Trials

- The United States Department of Health and Human Services through SAMHSA http://oas.samhsa.gov

- US National Institute of Drug Abuse

- US National Institute of Health

- The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research

- The National Cancer Institute

- The UK NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care

- The UK Office for National Statistics ons.gov.uk

- The US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention

- The Cochrane Library

3.2.2 Search Term Used

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken for sources that has “tobacco use” or “smoking” associated with terms “young people”, “statistics”, “prevention”, and “prevalence”.

3.3 Study Selection

The studies were selected initially from their titles, summaries, abstract whenever available. If two or more sources are related, the most up-to-date copies containing the full text of the studies was selected to avoid duplication and confusion. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) have been implemented to get the optimum data extraction in this systematic review.

The Data Extraction and Study Selection Form used are delineated below:

[Directly extracted from Cochrane CFGD November 2004]

Study Selection, Quality Assessment & Data Extraction Form

| First author | Journal/Conference Proceedings etc | Year |

|

|

Study eligibility

| RCT/Quasi/CCT (delete as appropriate) | Relevant participants | Relevant interventions | Relevant outcomes |

| Yes / No / Unclear | Yes / No / Unclear | Yes / No / Unclear | Yes / No* / Unclear

|

* Iissue relates to selective reporting – when authors may have taken measurements for particular outcomes, but not reported these within the paper(s). Reviewers should contact trialists for information on possible non-reported outcomes & reasons for exclusion from publication. Study should be listed in ‘Studies awaiting assessment’ until clarified. If no clarification is received after three attempts, study should then be excluded.

| Do not proceed if any of the above answers are ‘No’. If study to be included in ‘Excluded studies’ section of the review, record below the information to be inserted into ‘Table of excluded studies’. |

References to trial

Check other references identified in searches. If there are further references to this trial link the papers now & list below. All references to a trial should be linked under one Study ID in RevMan.

| Code each paper | Author(s) | Journal/Conference Proceedings etc | Year |

| A | The paper listed above | ||

| B | Further papers | ||

Participants and Trial Characteristics

| Participant characteristics | |

| Further details | |

| Age (mean, median, range, etc) | |

| Sex of participants (numbers / %, etc) | |

| Disease status / type, etc (if applicable) | |

| Other | |

Trial characteristics

see Appendix 1, usually just completed by one reviewer

Methodological quality

We recommend you refer to and use the method described by Jϋni (Jϋni 2001)

| Allocation of intervention | |

| State here method used to generate allocation and reasons for grading | Grade (circle) |

|

| Adequate (Random) |

| Inadequate (e.g. alternate) | |

| Unclear | |

| Concealment of allocation Process used to prevent foreknowledge of group assignment in a RCT, which should be seen as distinct from blinding | |

| State here method used to conceal allocation and reasons for grading | Grade (circle) |

| Adequate | |

| Inadequate | |

| Unclear | |

| Blinding | |

| Person responsible for participants care | Yes / No |

| Participant | Yes / No |

| Outcome assessor | Yes / No |

| Other (please specify) | Yes / No |

| Intention-to-treat An intention-to-treat analysis is one in which all the participants in a trial are analysed according to the intervention to which they were allocated, whether they received it or not. | |

| All participants entering trial | |

| 15% or fewer excluded | |

| More than 15% excluded | |

| Not analysed as ‘intention-to-treat’ | |

| Unclear | |

Were withdrawals described? Yes No not clear

Discuss if appropriate…………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Data Extraction

| Outcomes relevant to your review Copy and paste from ‘Types of outcome measures’ | |

| Reported in paper (circle) | |

| Outcome 1 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 2 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 3 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 4 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 5 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 6 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 7 | Yes / No |

| Outcome 8 | Yes / No |

| For Continuous data | |||||||

| Code of paper |

Outcomes (rename)

| Unit of measurement | Intervention group | Control group | Details if outcome only described in text | ||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||||

| A etc | Outcome A | ||||||

| Outcome B | |||||||

| Outcome C | |||||||

| Outcome D | |||||||

| Outcome E | |||||||

| Outcome F | |||||||

| For Dichotomous data | |||

| Code of paper | Outcomes (rename) | Intervention group (n) n = number of participants, not number of events | Control group (n) n = number of participants, not number of events |

| A | Outcome G | ||

| Outcome H | |||

| Outcome I | |||

| Outcome J | |||

| Outcome K | |||

| Outcome L | |||

| Other information which you feel is relevant to the results Indicate if: any data were obtained from the primary author; if results were estimated from graphs etc; or calculated by you using a formula (this should be stated and the formula given). In general if results not reported in paper(s) are obtained this should be made clear here to be cited in review. |

References to other trials

| Did this report include any references to published reports of potentially eligible trials not already identified for this review? | ||

| First author | Journal / Conference | Year of publication |

| Did this report include any references to unpublished data from potentially eligible trials not already identified for this review? If yes, give list contact name and details | ||

Appendix 1

| Trial characteristics | |

| Further details | |

| Single centre / multicentre | |

| Country / Countries | |

| How was participant eligibility defined?

| |

| How many people were randomised? | |

| Number of participants in each intervention group | |

| Number of participants who received intended treatment | |

| Number of participants who were analysed | |

| Drug treatment(s) or cognitive-behavioural techniques used | |

| Dose / frequency of administration | |

| Duration of treatment (State weeks / months, etc, if cross-over trial give length of time in each arm) | |

| Median (range) length of follow-up reported in this paper (state weeks, months or years or if not stated) | |

| Time-points when measurements were taken during the study | |

| Time-points reported in the study | |

| Time-points you are using in Meta-View | |

| Trial design (e.g. parallel / cross-over*) | |

| Other | |

* If cross-over design, please refer to the Cochrane Editorial Office for further advice on how to analyse these data

References:

- Jϋni P, Altman DG, Egger M.. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001 Jul 7;323(7303):42-6.]

3.4 Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs):

“Description of intervention and controlled conditions in RCTs of youth smoking cessation interventions

| Author Year (name of intervention) | n | intervention description | control |

| Based in Schools | |||

| Sussman 2001 (Project EX) | 335 | CBT for students in alternative high schools with school based clinics 8 classroom based sessions, 6 weeks OR 8 classroom based sessions, 6 weeks with School-As-Community | No intervention |

| Robinson 2003 (Start to Stop) | 261 | Behavioral interventions for students caught smoking based on social influence model and stage of change 50 min individual stage-based intervention x 4 weeks + monthly calls x 12 months | “I Quit” pamphlet + monthly calls x 12 months |

| Adelman 2001 | 74 | Smoking cessation curriculum based on American Lung Association Tobacco Free Teens and American Cancer Society Fresh Start 8 classroom-based sessions x 50min, 6 weeks | Information Pamphlet |

| Pbert 2006 | 1148 | CBT based on US Public Health Service “5 A model” delivered by school nurses 2 x 30min and 2x 15min sessions over 1month | Usual Smoking cessation care” |

TABLE: 1: Randomized Controlled Trials

[Directly extracted from Drogues, sante et societe, Vol. 6 no 1, juin 2007 Supplement II Available at A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials of Youth Smoking Cessation Interventions by Andre Gervais et al (2007)]

3.4.1 Randomized Controlled Trials of Youth Smoking Cessation Interventions

Sussman 2001 (Project EX): Sussman et al (2002) have evolved through systematic review that an approximate average smoking quit proportion of 12% with 3-12 months continued follow ups in intervention cases whereas only 7% in controlled group cases. However under the current scenario Sussman et al (2006) have administered a statistical assessment of 48 controlled live cases amongst which only 19 were RCTs and hence developed the theory that smoking cessation schedules have encouraged immediate complete quitting of about 3% in addition inspired the people’s desire towards quitting to about 46%. Moreover involving school students in tobacco control programmes like moulding through motivation enhancement, cognitive-behavioural methodologies and advances through social impact in five continued schedules have produced much higher quit results. Very lately the Cochrane collaboration analysed six RCTs, seven cluster-randomized controlled trials, and two non-randomized controlled trials that assessed the effectuality of the cessation schedules with six months’ follow-up programmes monitoring smoking habits. Cases pertaining to transtheoretical practical model proposition which has yielded average long-lasting achievement enduring with continuous two-years’ follow up study. Cognitive behavioural healing cure mediation generated essential efficacies when varied results developed were merged on account of combined studies.

Of the RCTs that abided by the inclusion criteria are Sussman 2001 (Project EX), Robinson 2003 (Start to Stop), Adelman 2001, Pbert 2006 – they carried out cessation programmes with school students under clinical settings. Abstinence was quite evident in cases of Sussman 2001 and Robinson 2003. However drop-out rates could be captured in the study of Robinson et al (2003) as 8% in only a month’s behavioural monitoring schedules to resurface students caught smoking who were then rehabilitated to quit.

3.4.2 Appraisal of Studies

The evaluation generally selected studies in terms of credibility, study design quality, and freshness of contents. However, these factors are only serves as general guide to quality as each study may be designed with specific strengths and weaknesses.

3.4.3 Limitiations of the Review

This study has used a structured approach to ensure quality outcome but it also acknowledge the few inherent limitations associated with systematic reviews. The quality of this review is thus limited by the quality of the studies selected along with the inherent weaknesses of the review methodology itself.

Another limitation is the restriction in language as only studies that are in written in the English language were considered. This restriction limits the scope of the study to the United States and United Kingdom. In addition, the review was limited to the published academic literature and did not have the opportunity to review unpublished works. Although majority of the studies were read and analyzed for inclusion, there may be equally relevant studies that were overlooked during the search.

Finally, data extraction, critical review, appraisal, and report preparations were carried out by a lone reviewer over a limited timeframe thus the reader is advised to consult the original sources cited for more details

Chapter: 4

4.1 Findings

4.1.1 Johnson et al. (2009) –A School-based Environmental Intervention to Reduce Smoking among High School Students: The Acadian Coalition of Teens Against Tobacco

The intervention, a randomized, controlled study is a school-based environmental program involving teachers and all students in the 19th grade. It was implemented in 20 schools located within south central Louisiana in the United States.

The ACTT intervention programs include teacher workshops in which they received most up-to-date information about tobacco use and were encouraged to support the intervention program and persuade their students to participate. A school-based media campaign through posters and public service announcement were implemented to deliver positive modeling, verbal and pictorial persuasion. The media campaign used different theme each academic year that varies according to the budget level of the campaign. Low budget media campaign are those obtained from CDC and the American Cancer Society free of charge while medium and high budget media campaign consist of materials developed inside the campus and implemented by social marketing firms respectively.

The intervention was originally as cohort study but due to the difficulty capturing classroom time, the program was changed to an environmental intervention where the entire student body is the target. The activities of the intervention program such as the media contest, quiz and video were conducted at the rate of 1-2 per months and actively delivered to target audiences. However, since the school wide activities were limited to the school’s main hallway during lunchtime, the participation rates were considerably lower when compared to the total number of students in the school.

The implementation of the intervention was assessed for fidelity, exposure, impact, reach, and environmental context. Fidelity in the sense that activities were delivered as planned through observation and key components checklist. Reach is determined by the quantity of students attending a particular activity. For instance, for classroom presentations such as introduction and video, reach is considered the actual number of participants while an ‘estimate’ when measuring activities in hallways. Exposure and impact on the other hand were measured with via student survey. Environmental context such as hurricane or turnovers of health educators associated with the program were considered barriers.

In this study, the school was the unit of randomization and analysis. Mean, medians, and frequencies were employed to sum up the data. The Fisher’s exact test and t-tests were used to evaluate the differences in the baseline group. The prevalence of 30 and 7 days smoking were computed for each of the 20 schools while group intervention and year differences in prevalence were evaluated with mixed models repeated measures ANOVA.

The result yields the information that there were more students in the control group relative to the intervention group. White dominated the sample for 9th and 12th grade with mean age about 15 years for both intervention and control groups. Moreover, there more females than males for both intervention and control groups.

The 30-day prevalence of cigarette smoking for intervention and control over the four years of the program for 9th grade was 23% (for intervention schools) and 26.1% (for the control schools) at baseline. The variation in prevalence between these schools at baseline was insignificant considering the fact that there were no intervention activities during the first year. However, when activities began in the second year of the program, the prevalence in the intervention schools dropped by about 2% at 21.9% and rose in the control schools to 30.7%. In the next year of intervention, prevalence unexpectedly increased to 24.1% in interventions schools and 31.3% in control schools, which is over 1% rise in the baseline. In the final year of the program, the 30-day prevalence between intervention and control schools was 7% (27.3% for intervention schools and 34.3% for control schools).

Similarly, the 7-day prevalence yields almost the same results. In the first year, prevalence in intervention schools was 14.8% while 17.2% in control schools. In the second year, prevalence increase by 1.2% for intervention schools and 5.6% in control schools. In the third year of the program, prevalence in intervention schools was at 16.2% and 23.8% for control schools. The increase marked the 7.6% difference between intervention and control schools. In the fourth and final year of the program, the increase in prevalence was as high as 9.9% for control school and 6.4% in intervention schools.

Assessment of 30-day prevalence by individual schools reveals that only five schools (4 in the intervention and 1 in control schools) showed reduction in prevalence over the fours of the program. All the schools showing reduced prevalence were mostly African-American while no decrease was recorded with any of the white schools.

The absence of significant effects was not from deficiency of the study design since it is based on a well-accepted standard for school-based randomized trial in the United States. Secondly, the randomization scheme was suitable based on the available information. However, although there are some advantages of the environmental program since exposure is bigger compared to classroom-based, it may have been affected by the limitations of an environmental program. For instance, low participation rates in hallways activities, lack of program recognition, weakened budget affecting the value of student incentives, and decreased importance in the school routine may have reduced the effectiveness of the program. This is because there are evidence to suggest that activities done inside the classroom capture more audience and had greater participation that those activities done in the hallways. Activities such as these particularly when it becomes a lunch time affair can affect the number of participation since those students who are already smoking are least likely to attend such activities. Therefore, a significant number of students who actually need the intervention were missed resulting to low program dose.

Another problem why the program did not attain its goals is the fact that the program’s budget was not originally intended for the entire student body. The budget was not enough to produce quality gift and incentives that could encourage students to participate.

4.1.2 Campbell R. et al. (2008)- An Informal School-based Peer-led Intervention for Smoking Prevention in Adolescence (ASSIST): A cluster randomized trial

Two hundred twenty three secondary schools in the west of England and Southeast Wales were invited to participate in the ASSIST open cluster-randomized controlled trial in February 2001. ASSIST or “A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial” intervention was an adaptation of previous initiative promoting sexual health. ASSIST on the other hand aimed to spread and sustain new norms of non-smoking behavior on young people aged 12 to 13 years by creating a social network in schools.

Out of the 223 invited schools, 113 responded positively but only 66 were selected. However, only 59 schools signed in and agreed to continue with their existing smoking education program and policies, and to be randomized by control group or by intervention group. To avoid being a classroom-based, ASSIST strategically select and trained influential students to act as peer supported during information interactions outside the classroom. In this manner, peer supporters can encourage their peers not to smoke. Influential students were identified through a nomination questionnaires sent to students in both intervention and control schools.

Ten thousand seven hundred thirty students aged 12-13 years in 59 schools in England and Wales went under the ASSIST cluster randomized controlled trial. 5,372 students from 29 schools were randomly assigned by stratified block randomization to the control group while 5,358 students from 30 schools to the intervention group. Outcome data were gathered at baseline from September 20, 2001 to February 12, 2002, January 30, 2002 to May 27, 2002 just after the intervention, after a year follow-up from November 28, 2002 to May15, 2003, and after two-year follow-up from November 18, 2003 to May 12, 2004 with questionnaire completed in the classroom. Two weeks before every data collection, schools involved in the study circulated to all parents and carers information regarding the program along with a reply slip that has to be returned if they did not wish their child to participate. Consequently, those students that were withdrawn by their guardians or parents did not take part during the data collection stage for students in the relevant year group.

All participating students provided saliva samples and were give questionnaires about smoking behaviors. The samples were analyzed with ELISA Technique to evaluate the frequency of misreporting. The study also explored teacher’s opinion of the intervention and examined the views of peer supporters about their roles and their actions with reference to these roles. Moreover, to determine the role of the social network in the propagating the intervention and distribution of the peer supporters within their year groups, data about the participant’s social networks were gathered. The cost of the intervention was also considered and staff time, travel time and distance, consumables, accommodation, and so forth were being recorded on weekly basis. Statistical analysis was done based on the 1998 Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Survey in Wales. Consequently, it was assumed that 30% of students were in the high-risk group of smoking initiation and 30% were assumed to smoke each week with an intra-cluster correlation of 0-02.

The results of the study shows 90% of eligible students provided self-reported data for smoking despite some problems. Two schools withdrew after randomization because management of the schools suddenly changed decisions to participate but those in list of interested schools replaced them. Out of the 11,043 students in 59 participating schools, 3% were withdrawn by their parents before data gathering at baseline. One school closed after the follow-up was taken after the intervention while one school close after the first year follow-up. However, majority of students from these schools were not lost to follow-up as out of the 123 students enrolled in these schools, 117 were transferred to schools involved in the trial.

Some differences were noticed between the characteristics of schools at baseline as more students in schools under the control groups reported smoking each week. There was no significant differences noticed between intervention and controls schools in terms of students occasional and experimental smoking behaviors. 16% of peer supporters who completed their training achieved the expected target of 15% of the year group as they are generally fitted for the particular group in terms of sex, ethnic origin, and smoking status. Retention rates were also high for those students who were trained and willing to work continuously as peer supporters at 99% while 84% submitted their completed diary at the end of the intervention period.

In general, smoking rate for all year group increased from 5. 7% at baseline when the students were aged 12 to 13 years to 13.8% in the first follow-up, 20.3% in the second follow when the students were already 14 to 15 years of age. Prevalence of smoking was less in interventions schools for all three follow-up points. In the first follow-up, the odds ratio of being smoker was 95% with schools in the intervention group. However, the odd ratio was not significant in the 2nd year follow-up indicating that reduction in intervention has an immediate effect. Results for high-risk group, the odd ratios were at 0.56 to 0.99 in the first follow-up and 0.70 to 1.02 in the second year follow-up. These ratios suggest that the intervention had no considerable impact on students identified in the baseline as occasional and experimental smokers. Results of the comparison between self-reported smoking data and salivary cotinine content suggest that students self-reporting accuracy is 99% since only 1% of salivary cotinine had been found. The average cost of the intervention was £27/student or £4,700/school.

Overall, the study demonstrated that the ASSIST training program is an effective tool to achieve and sustain reduction in uptake of regular adolescent smokers for 2 years after its delivery. The peer-led intervention was well received by students and schools evidenced by the high response rate of over 90%, the retention of all schools, and the consensus shown between self-reported smoking data and salivary cotinine. In addition, the ‘external trainer’ approach that deliver training program through independent trainers outside the school, was also well received by students and school staff and contributed to young people’s sense of ownership of the intervention. The exploitation of informal channels of information and peer influence help the intervention reach those that are more susceptible to non-smoking messages.

4.1.3 Liu et al. (2007) – Addressing Challenges in Adolescent Smoking Cessation: Design and Baseline Characteristics of the HS Group-Randomized Trial

This smoking cessation intervention utilized multiple strategies to address known barriers in tobacco use intervention programs through proactive identification of smokers in the population and direct approach to encourage participation. It has invited both smokers and non-smokers and proactively delivered the intervention to protect smoker’s privacy. It tailored the intervention to participants and communicated respect for adolescent and their choices.

The intervention is base on Social Cognitive Theory and incorporated Motivational Interviewing to enhance smokers’ own motivation and will for quitting smoking. It has also utilized cognitive behavioral skills training to build skills for smoking cessation and relapse prevention. The reason given for choosing Motivational Interviewing was its potential to reduce smoking using non-judgmental and non-prescriptive approach.

Since privacy is one of the intervention’s strategy and many teens have easy access to a telephone, intervention was delivered via counselor-initiated telephone calls. The study believed that telephone counseling could provide privacy and personalization of face-to-face counseling at a lower cost. In addition, through proactive telephone interventions teens’ participation is easy and allows all smokers to be involved including those infrequent smokers that are typically overlooked by cessation programs for teens. Moreover, teens’ receptivity is enhanced by tailored content and dose since it increases relevance to specific smoker. Consent for intervention participation, particularly those at minor-age, from parents was taken through mail with telephone follow-up. Smokers in the trial were selected through a confidential baseline survey before being invited to participate. The proactive approach according to the study provides the opportunity to recruit a range of adolescent smokers.

Fifty high schools were randomly selected from one hundred sixty eight Washington State public high schools that met the study’s eligibility criteria. Out of the 50 selected schools, 93.1% of high school junior went a baseline survey. Those with schools with foreign students who were unable to read or understand English were eliminated from the survey – 1,188 high school juniors in total. Smokers who were smoking for the last 30 days and been smoking at least monthly were included based on their answers of three primary survey questions. These are those who answered “once a month or more” on how often they smoke cigarettes, responded ‘yes’ on using one or more cigarettes in the last 30 days, and answered ‘within the past 30 days’ when asked the last time they smoked or tried a cigarette. The study capitalizes on the existing social network and positive social interactions and includes non-smokers who reported that they have smoking friends, interested in learning more about quitting, and willing to do whatever they can do to help friends stop smoking. In total, 2,151 smokers and 743 non-smokers were identified and selected for the intervention.

The high school was chosen as the experimental unit to prevent contamination due to social mixing of intervention-exposed students and unexposed students, enable wider reach, and capitalize on the smoker’s interaction. The randomization of schools was pair-matched by prevalence of smoking, number of smokers, cessation stage and percentage of student’s eligible for free/reduce-price school meals. The matched random assignment was performed via a computerized coin flip for each randomly ordered pair. Trained study staff with scripted explanation of survey procedures and study information administered the in-class survey in regular classrooms. To ensure the accuracy of self-reporting of smoking behavior, make believe saliva samples were taken. Students who were absent during the initial survey were contacted for an in-class clean-up survey 2 weeks after and those who cannot come were asked to complete the survey questionnaires by mail.

Collection of baseline data was done on both schools and students. The Survey of High School Principals provided the information required on school demographics and smoking-related characteristics such as rural or urban composition, staff smoking, etc. Similarly, to collect baseline information on older teens’ smoking and to identify potential participants for the trial, data from the Survey of High School Juniors was utilized.

Permutation-based methods were used to evaluate the intervention. This is to find out the differences between the two arms in endpoint outcomes. The permutation method of analysis acknowledges the intra-class correlation within individuals in the same schools by permuting school, as opposed to individual, among set of all possible intervention assignments, to calculate the test statistics and form a null distribution. The test static observed based on the actual assignment is then referenced against this null distribution for hypothesis testing. This analytic method avoids modeling and distribution assumptions, relying solely on the random assignment of intervention, and is flexible for covariate adjustments. Analysis of subgroups was also conducted based on strong empirical or theoretical evidence to detect differential intervention impact in specific subgroups.

The sample size calculation were done taking into account the group nature of the experimental unit and accounted for the within-school intra-class correlation. The sample size calculation used the following parameters. First, 6-month abstinence rate of 0.06 at the study endpoint in the control group. Second, 90% participation rate in endpoint data collection, based on prior experience on the Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project (HSPP), a 12-year trial on adolescent smoking. The third, interclass correlation coefficient for cessation among high school senior smokers, conservatively estimated to be 0.025 from prior HSPP data on cessation among high school seniors. Fourth, resulting variance inflation factor of 2.11. Fifth, two-sided test that accommodates the intra-class correlation and sixth alpha = .05. Therefore, the trial seems to include sufficient schools and participants to evaluate properly the effectiveness of the intervention.

The trial used a “wave’ design in which recruitment of high schools and subsequent activities were phased-in over 3 years. Fourteen high schools with 515 smoke trial participants were recruited in the first year -2002), 20 schools with 966 smokers in the second year and 16 schools with 670 smokers in the third year. The HS Study intervention, experimental design, procedures and instruments were reviewed and approved by the Hutchinson Centre’s Institutional Review Board.

For the baseline results, the percentage of valid data range is from 86% to 100%. Average enrolment for the 50 participating high schools is 1,224 students, ranging from 204 to 2,376 students. An indication of the school’s status is the percentage of students eligible for free or discounted price school meals. The average of this percentage for participating schools was 24.6%. 50% of families in 21 high schools lived in rural areas. 49% of the 12,141 baseline survey respondents were females, 73.5% White, 7.2% with multiple races or ethnicity, 6.4% Asian, 6.1% Hispanic, 2.9% Black, and the rest is either Pacific Islander or American Indians. Majority of the survey participants were at age 16 or 17 at the time of survey or 94% while only 4.9% were older than 17. Smokers in these high school juniors is around 2,175 or 17.9% and 6.8% or 794 were identified as daily smokers.

The study found that smoker trial participant’s smoking patterns were different. The cumulative use of cigarettes however showed that 52.4% have smoked in excess of 100 cigarettes and concerning smoking frequency, students who smoke at least daily gathers 37.2% compared to 62.8% of those who smoke less daily. However, the study found 69.9% of smokers were generally having strong motivation to quit while 30% lacked motivation.

Examination of results reveals that smoker’s trial participants in experimental and control conditions were very similar with regard to most characteristics with the exception on the percentage of daily smokers which were 39.9% in experimental compared to 34.5% in control. However, although there have been some variations in the smoking frequency among smokers, almost 60% of daily smokers were past quit attempts compared to 34.2% of less-than monthly smokers and 36.5% of monthly-but-not-weekly smokers. Majority of those who smoke less-than-monthly has no intention to smoke in the future at 73% compared to 48.8% of daily smokers who do not have plans to quit. In general, those who smoke more frequently got no motivation to quit and lower self-efficacy for quitting.

Considering the size of the population involve in the intervention, the HS Study perhaps is the largest group-randomize trial in adolescent smoking compared to the last two intervention discussed. The design of the intervention generally aims to overcome difficulties commonly identified in adolescent smoking literature. For this reason, it has several new features not found in standard programs. The inclusion of “proactive” identification of smokers and use of a liberal definition of smokers help expand the intervention to cover even low-frequency adolescent smokers and those that were unmotivated to quit.

According to the author, the HS Study is the first population-based survey to use proactive approach in identifying and recruiting participants, and the first intervention to target daily and less-than-daily smokers as well. The proactive identification evidently enables the study to carry out its functions without breaching the rights of individual and confidentiality of private information. Having both smokers and non-smokers in the trials undoubtedly gave the intervention the opportunity to use the non-smoking participants as a tool to help their smoking friends to quit. Significant advantages were added by the “Phase-in” or “Wave” design as it enables project staff to participate fully in recruiting and establishing important collaborative relationships with schools and reduce the annual cost of the study. In addition, it enables interim evaluation of the intervention process and incorporation of refinements into subsequent waves as required.

The intervention’s design innovations have enabled the study of mixed population of older adolescent smokers with different rate and frequency of smoking, varying level of motivation to quit, and different degrees of receptivity to cessation assistance. The baseline information gathered from these diverse types of smoking behaviors not only enhanced the study’s understanding of young smokers but also highlighted intervention-related issues and challenges that may be useful for future interventions. For instance, the fact that over one-third of less-than-daily smokers were making an attempt to quit in the past 12 months and the difference in quitting behaviors and beliefs between infrequent smokers and frequent smokers.

Assessing by the Study screening form, Data extraction form, Quality assessment process the following SYSTEMTIC REVIEW format/framework has been tabulated below:

Table: 2

| Author Year (name of intervention) | PARTICIPATION | intervention description | RESULT AND control |

| Based in Schools | |||